Chijioke John Ojukwu, décembre 2013

Did Martin Luther King’s idea of a Beloved Community die with him?

An exploration of the turn towards racial separation in the civil rights movement and the pursuit of reconciliation through the Freedom Seder.

Mots clefs : Elaboration et utilisation du symbolique | Respect des droits humains | S'opposer à l'exclusion sociale | Martin Luther King

Introduction

That the death of an individual can constitute a catalyst for peaceful social change, civil war and even genocide reveals the enduring value and precariousness of human life and the complexity of human agency, which demonstrates the intersection between the personal and the political. At first glance, the assassination of Martin Luther King seemed to expose the power of violence to contend and extinguish, momentarily, the human aspiration for freedom and justice that found voice in the life and thought of King and the wider Civil Rights Movement. This is to say that the bullet that claimed King’s life reinforced the instrumentality of violence as an act that threatens human dignity and personhood, both of which King had creatively juxtaposed with an ethic of reconciliation in his theological vision of the Beloved Community (Willis, 2009). This is the point that former Black Panther member, Eldridge Cleaver (1995, 171) makes when he lamented that the assassin’s bullet claimed “a period of history, a dream and a hope”; although Cleaver(1995) was less specific about the content of King’s dream and its consonance with his ideological position. In addition, the assassination of Martin Luther King demonstrated the power of violence, in terms of its limited nevertheless actual capacity, to interrogate and disrupt the commitment of an oppressed people to a nonviolent struggle and to reconciliation, as can be observed in the tide of racial riots that followed (Risen, 2009; Fairclough, 2001). This further revealed the mechanism in which violence reproduces and reinforces itself through a cycle of retaliation and uncontained rage in the absence of a rhetorical and embodied interpersonal and communal forgiveness. That being said, the riots that erupted in the wake of King’s violent death should be understood contextually and in its spontaneity: as an outlet of a deep seated frustration of black anger (Nick; 2005; Burns, 2011) rooted in Kings’ symbolic role as the embodiment of the dream of an oppressed people to realise justice, and in the historical wounds of racial oppression. This lends veracity to Vincent Harding (2013) point that the death of King “broke the heart of many”: a point that is pertinent in understanding the role of King’s assassination in the Civil Rights Movement, given the pervasive presence of racial riots in the American experience as a symbolic locus where the struggle to live together harmoniously is most visibly dramatized (Gilje, 1996; Olzak, 1992).

Rabbi Rothschild’s (1968 cited in Rothschild Blumberg, 1985, 203) eulogy at King’s memorial service casts a light on the anger behind the riots that erupted in the wake of the assassination:

“Do we reject the potential apartheid that threatens to take over our land? Then we must be willing to admit the Negro into the structures of our white society. Do we deploy violence? Then we must be willing to remove the cause of violence-the denied hopes, the unfulfilled dreams…..”I have a dream”, once cried Martin Luther King. Now that dream is dying in too many souls.

For one thing, the presence of a Jewish Rabbi at King’s memorial service was a public demonstration of the possibility of transcending racial and religious barriers in a segregated society. As a testament of the inclusive character of the Civil Rights Movement, it provided a glimpse into King’s Dream of a Beloved community where race did not determine the boundary of belonging between people. However it is the poignancy of Rothschild words to capture the death of King’s dream for a Beloved Community in his impassioned lament that the “dream is dying in too many souls” that captures the impact of this tragedy. At the same time, the riots and spontaneous outburst of violence also exposed King’s estrangement from the community in which he was held dear, paradoxically, in that it clearly demonstrated that King’s commitment to nonviolence and reconciliation did not hold universal currency in the Civil Rights Movement. In essence, it is to say that the violence represented a departure from the commitment to reconciliation and the triumph of rage and vengeance over forgiveness, especially in light of the fact that its targets were not directly implicated in King’s assassination but were rather conceived as symbolic embodiments of racial injustice.

To make this point is not to deny the authenticity of the anger behind the riot as an impassioned lament of King’s death but to recognise that as a form of political expression, the riots which followed King’s assassination remained in tension with his commitment to realising the idea of a Beloved Community without violence.

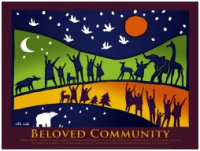

Making Sense of the Beloved Community

Whilst the concept of the Beloved Community was first articulated by the American philosopher Josiah Royce, it is the late Civil Rights leader, Martin Luther King that injected new life and meaning into this concept (Marsh, 2005) catapulting it, explicitly, into a concrete context of nonviolent socio political change, as an enduring metaphor and symbol of an inclusive reconciled human community (Chinula, 1997; Baldwin, 2005). To be acquainted with King’s Beloved Community and its meaning in the context of the Civil Rights Movement is to be firstly initiated into the rivers of African American history where the narratives of slavery and legislated segregation intermingle with stories and songs of courage, forgiveness, resistance and hope (Davis; 2012; Bennett, 1993). In essence, this bitter-sweet experience poetically described as a creative exchange by Victor Anderson (2008) is not exhausted by physical suffering. Rather, Kortright Davis (2012, 93) envisions it as a tale of “ebony compassion and grace” , where those considered the “wretched of the Earth” have struggled to affirm their humanity and sustain love in their heart in the face of uncommon cruelty. Therein lies the strange paradox of the black experience where King’s lived experience is situated: precisely at the juncture where the music of discord and violence echoes, another harmony of, what Cornel West (1999) calls “black love” resonates, bearing witness to the possibility of love to overcome enmity. However, while it is true that this tale of “ebony compassion and grace (Davis, 2012) cannot be reduced to suffering or the primacy of racial identity (Anderson, 2008), it is primarily the unjust suffering of injustice rooted in the myth of racial supremacy which marks the social context where King’s Beloved community is located. In foregrounding the cruelty of slavery and the social dislocation it produced, Davis (2012, 111) characterises this struggle as a pathos of “homeless existence” which finds voice in the line from the Negro Spiritual, “Sometimes I feel like a Motherless Child.” At the heart of this homeless existence (Davis, 2012) is the question over the humanity and personhood of an oppressed people which are considered non-existent because of the colour of their skin, therefore making them eligible for non-participation in the circle of human communion. As Cornel West(1999, 101) puts it, “every major institution in American society -churches, universities, courts, academies of science, governments, economies, newspaper and magazines, television, film and others- attempted to exclude black people from the human family in the name of white supremacy”. To be specific, this systematic exclusion in its contextual particularity in the South where King grew up entailed a social and economic character which created nurtured and institutionalised inequality and poverty (Davis, Gardner and Gardner, 2009; Bennett, 1993). However, it is precisely the fracture of interpersonal relations between the races, and the crises of race relations it created by virtue of the de jure and de facto segregation that King invokes his dream of a Beloved Community.

King’s vision of the Beloved Community begs a careful and critical analysis precisely because its meaning resides in the intersection between the interpersonal, political and theological. For Charles Marsh (2005, 2) the content of the Beloved Community is theologically specific, envisioning the “realisation of divine love in lived social relations” in a society where people are divided by centuries of oppression and hate. Marsh (2005, 2) conceives the Beloved Community as a “sustaining spiritual vision” of the Civil Rights Movement which calls forth overcoming hatred with love and creating spaces of reconciliation. In consonance with Marsh’s emphasis on its theological content, Hetzel (2009, 296) claims that:

“God’s love for creation disclosed in the event of Jesus Christ becomes for King the foundation for the human effort to realize a deep democracy. The political task, according to King, was to translate Jesus’ teaching of the Kingdom of God into a beloved community on earth. Thus, King’s contribution to America’s political future was first and foremost theological”.

At the heart of the Beloved Community is a dynamic interface between an ethic of mutual belonging, which can be said to be rhetorically embodied in “I belong to you” and a corresponding affirmation of human dignity rooted in a Christian theological tradition that affirms human personhood as the creation and subject of divine love. Chinula (1997, 33) calls this affirmation of human dignity a “somebodiness”, which he conceives both as being metaphysical by virtue of being created in God’s image, and socio political; the latter grounded in the presence of social justice. This presupposes that the Beloved Community is in tension with social and political structures that assault human dignity (Willis, 189) and that it embodies a sense of “human togetherness and solidarity (Chinula, 1997) rooted in an ethic of mutual belonging. Mutual belonging implies that the essence of the human person is located in a relationship with God and one another that is grounded in love. To put it differently, the Beloved Community presupposes that the human person has inherent value and dignity that corresponds with a capacity to demonstrate love concretely in a lived experience. King locates this ethic of love on the Christian drama of the cross which he construes as “the eternal expression of the length to which God will go in order to restore a broken community.”

On the other hand, Ingwood (2009) argues that the meaning of the Beloved Community is foremost predicated in the African American experience where King is socially and politically situated as a member of an exiled and oppressed community forced to make sense of dislocation. According to Ingwood (2009), the Beloved Community is grounded in the particular geographic and social dislocation of the African American community that King represents symbolically, which severs the bonds of belonging between an enslaved people and their land of origin:

“Dr King’s philosophy emerged from the black Atlantic experience to reinvent the spatial order of US society. This is to say that King’s positionality, in a post-slave context, was informed by a history of dispossession—mentally, physically, emotionally, economically, culturally—and black Atlantic routes. The black Atlantic experience of dislocation leads to a re-imagining of the geographic possibilities. In other words the expanded black Atlantic becomes a wellspring from which to draw to remake and re-imagine the geographic realities of life in the Jim Crow South which becomes central to Dr King’s philosophical and spiritual spatial articulations. The contradictions which are part of the experience of growing up in the Jim Crow South are central to King’s notions of community”.

Ingwoods’ perspective is very useful in shedding light on the social context where King invokes the Beloved Community because it allows us to see that segregation created a wall (Bennet, 1993) of division between two unequal worlds. It is in this sense that it underscores the centrality of love and reconciliation in the Beloved Community given that the legacy of slavery and the direct and structural violence of the Jim Crow Laws fractured race relations significantly, consequently creating a barrier for meaningful interracial relations devoid of subordination.

As an implicit call for reconciliation which transforms this malaise, the Beloved Community facilitates and anticipates an overcoming of historical and present enmity between members of a divided community through human agency grounded in divine Love. For King, however, love is no less pragmatic, abstract or ethereal but is the central action of change (Lewis, 1995, 74) grounded in a worldly context of social and political change. Love inscribes a transformative character to nonviolent political action, which manifests in forgiveness and a desire for reconciliation, which overcomes social divisions and creates and preserves community (King; 1959, 99). That King acted as the child and symbolic representative of the Civil Rights Movement (Harding, 1979, 40) did not give him monopoly over this radical theological imagination in the Civil Rights Movement however. Nevertheless, one cannot devalue the role of King in legitimising this vision in the movement.

Rather the substance of the Beloved Community as an ethic of reconciliation situated in a divided society marked by systematic exclusion and discrimination permeated and pervaded the various local and national movements engaged in the struggle for racial justice: it was enshrined in founding documents, manifestos (Southern Christian Leadership Council, 1957of local movements in the struggle Student for Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, 1960; ) In the Birmingham manifesto ( www.crmvet.org/docs/bhammanf.htm), which stated the objectives of the Civil Rights campaign, one finds the: “the absence of justice and progress in Birmingham demand that we make moral witness to give our community a chance to survive. We demonstrate our faith that we believe that the Beloved Community can come to Birmingham”

It also found concrete expression in lived experience and dynamic of interracial relations during the Civil Rights Movement. To make this point is to re-construe nonviolence in the Civil Rights Movement as a phenomenon that transcended direct actions such as peaceful marches, sit-ins or demonstrations and to recognise that such nonviolent direct actions were situated in a larger context of “redemptive” interpersonal relations which created spaces of reconciliation. In particular, such patterns of reconciliation which interrogated the logic of white supremacy and its material embodiment in residential segregation were visibly enacted in the practise of hospitality and the sharing of private spaces and interracial commensality it entailed in the Civil Rights Movement. As a manifestation of the Beloved Community, such symbolic and nonviolent practises re-configured the apartheid structure of spatial segregation into a circle of belonging where members of a divided society could affirm their shared humanity functionally in vulnerable communion. What is being suggested here is that a culture of hospitality, which in some cases functioned as a praxis of sanctuary, given the reactionary violence that cocooned the Civil Rights Movement, embellished its nonviolent activism. To be clear, here the word sanctuary denotes in its basic meaning what Bloom and Farragher (2011, 4) describe simply as a “place of refuge from danger, threat, injury and fear. Linda Raben (2011, 44) considers such practices of hospitality in the context of political violence where human life is threatened a ubiquitous practise that constitutes a core part of our humanness. Trina Zelle (2007) describes it more poignantly in a way that lends deeper meaning to its manifestation in the Civil Rights Movement when she intimates that: “Sanctuary is perhaps the most significant form of hospitality -a welcoming of the rejected people whose very humanity has been called into question.” In other words, in the act of extending hospitality, a deeper transaction occurs in the economy of human relations which affirms the value of the guest or stranger as a human being.

This was clearly illustrated in the Civil Rights campaign for voting rights in Selma, Alabama that culminated in the Voting Rights Act, which Fairclough has described as the “crowning achievement of the Civil Rights Movement” (2002, 293). At its core, the Selma campaign in the Civil Rights Movement which brought together a network of local organisations including SNCC and SCLC was predicated on a pragmatic objective of the right to vote; nevertheless it also illustrated the Beloved Community in a tangible way that pointed to an alternative social order. In her personal narrative, Rachel West Nelson (1980, 51), who was nine years old at the Selma Campaign, fondly remembers the experience of hosting white visitor and Civil Rights activist, Jonathan Daniels as her moment of transformation, more like a catalyst that showed her that “there were really good white folks in this country, and with them on our side we would win our freedom. In this regard, in describing her friendship with the Civil Rights activist and episcopal priest she noted that:

“He was never a stranger, not Jonathan. From that first day he walked in with his suitcase and little knapsack, it was like an old friend coming home. We children loved him. He would smile at the way we talked, and we’d laugh at his speech. Jonathan would die for us.”

Similarly, Jonathan Daniels (1965), who became a martyr in the Civil Rights struggle in Selma, found the experience as much transformative and later described it as a living theology made him aware of the “living reality of the invisible communion of saints” and the possibility of whites and blacks living peacefully together as a beloved community:

“What we found there we sometimes think we shall see again only in heaven. The love before which we knelt in the morning would not again be visible at an altar, except to souls that had taken their first steps on the long trek out of the flesh.”

Interestingly enough, that West (1980, 132) describes the violent death of Daniels, who was shot by a local Sheriff, as an event that left a deep impression on her during the movement, discloses the measure of friendship which the two shared. The crucial point to be made here is that this interracial friendship which fostered the discovery of shared humanity and mutual belonging occurred in a spatially segregated precisely because of the hospitality of the host family who were willing to receive a stranger. It is in this light that the true significance of this hospitality, which created the platform for a meaningful encounter between members of divided societies, becomes more meaningful as a way of undermining a segregated spatial order predicated on exclusion.

The dream is dying, slowly

The movement away from the Beloved Community in the Civil Rights Movement, which tragically reproduced the racialised spaces of exclusion and its logic of violence that the Civil Rights Movement was intended to eradicate, cannot only be explained by the assassination of Martin Luther King. This is because prior to King’s death, the dynamics and substance of interracial and interpersonal relations within the Civil Rights Movement contained elements of exclusion and discrimination institutionalised in the status quo. For one thing, the marginalisation of the courageous and creative Civil Rights Activist, Bayard Rustin, which was also extended to women in some circles of the movement (Robnette, 1997), reflected the struggle to welcome and receive difference (otherness). In his case, it was precisely Rustin’s sexuality as a homosexual that placed him on the margins of the movement from the onset, which still persists in Civil Rights historiography, despite his monumental role in community organising and shaping King’s commitment to nonviolence (Garrow, 1986, 94, 140; Podair, 2009). That Rustin, the lost prophet, as John D’Emilio (2009) poignantly named him in reference to this scandal of invisibility, recently received the President Medal of Freedom from President Obama (www.whitehouse.gov/blog/0) only underscores the on-going struggle to recognise an inspiring peacemaker who laboured tirelessly to affirm reconciliation and brotherhood in the face of uncommon brutality. In the same vein, the emerging but belated focus and celebration of women in the Civil Rights Movement (Olson, 2001; Robnette, 1997; Holsaert, Noonan and Richardson, 2010) also brings to bear both the dynamic and active participation of women that enriched the struggle significantly and their corresponding struggle for recognition during and after the movement.

However, for major Civil Rights organisations like the Student Nonviolence Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), the decision to expel whites members signalled a movement away from the Beloved Community towards “racial separatism”. In many ways, the decision to expel the white members represented a negation of the commitment to reconciliation that the vision of the Beloved Community had conferred to the Civil Rights Movement. It also constituted a re-invention of a segregated order, in that it illustrated a desire to co-exist outside the framework of an interracial fellowship in shared spaces. Wesley Hogan (2011, 189) argues that a threatening and chaotic environment marked by violence and police brutality (246) strained the interracial friendship in SNCC, and that it created a growing disillusionment which obscured the possibility of the social change SNCC had envisioned. According to Hogan (2011) the reign of police brutality, rapes and white hostility to SNCC during the Freedom summer, loosened the bonds of friendship and interrogated the commitment to Nonviolence which had been the foundation for building a Beloved community. Taking Hogan’s (2011) perspective into consideration, it becomes clear that the power of human Love to realise Beloved Community in the face of unbearable inhuman cruelty should not be over exaggerated but should rather be asserted with the recognition that violence always tests such commitment and has the potential to produce a cycle of violence in its wake. This point is pertinent in the case of SNCC given the experience of State sanctioned terror which involved law enforcement agencies during the Freedom Summer.

In addition, in the cases of both SNCC and CORE, this ideological shift from a theological imagination of a reconciled community encapsulated in the Beloved Community, to Black Power embodied in an identity politics rooted in exclusion reflected the direction of the new leadership of both organisations. The subsequent leaders of SNCC Stokey Carmichael and H.Rap Brown were explicit in framing the Civil rights Movement through an identity lens of racial consciousness that invested political meaning to Blackness both as a call to self-determination and political and economic control, which they juxtaposed with a rhetoric of violence ( Hohle, 2013, 124; Murphree, 2006, 151; ). For CORE, this change in direction also reflected the new leadership under Floyd Mckissik and Roy Innis who proclaimed nonviolence as a “dying philosophy and expelled whites (Marable, 2007, 93). This implies that the movement towards an identity politics of racial consciousness conferred an abstract political character to the Civil Rights movement that negated and devalued a rhetorical and embodied affirmation of mutual belonging. In other words, it is can be argued that the ethical thrust of the Beloved Community embodied rhetorically in “I belong to you” and we belong to each other”, gave way to a self enclosed group solidarity and excessive individualism embodied in “I am black and I don’t need you”. This shift in emphasis devalued vulnerability and empathy, which remain integral to any meaningful social relations, and presented the Civil Rights Movement with an alternative language and praxis that differed significantly from King’s Beloved community. While the assassination of King fuelled the rise of groups rooted in Black Power such as the Black Panther, the roots of Black Power as a form of Black Nationalism that emphasised racial pride preceded King.

In the context of the struggle for racial justice in SNCC and CORE, the quest for an authentic space for cultural blackness understood in terms of a need to affirm and reclaim the humanity of an oppressed people obscured their own need to recognise their finitude and vulnerability both in terms of pragmatic organisational weaknesses, and need for relationship with those outside their group identity. This is not to deny that there was a genuine need to confront and to challenge the wounds of racial oppression, and to affirm a sense of self in the context of historical oppression. Rather it is to recognise that in ascribing priority to racial consciousness outside a vision of a reconciled humanity, the identity politics of racial consciousness falsely assumed that only the oppressed maintain a monopoly on compassion and empathy. In the context of SNCC, this made it easier to foster an attitude of distrust, suspicion and antagonism towards white participation. Consequently this created a lack of empathy that prevented some members of SNCC and CORE to appreciate, understand and celebrate the genuineness of white participation in the movement as a gift of love that greatly enriched the Civil Rights struggle for racial justice. In other words, in conceiving the presence of white participants as unwanted, and justifying their exclusion on grounds of a universal white racism and inability of whites and blacks to work together, SNCC re-affirmed the logic of racial separation which the Beloved Community negated. More specifically, the over politicisation of racial identity created a climate of distrust and suspicion that prevented interracial relationships from flourishing within the movement. According to Payne (2007, 388), such climate of bitterness and distrust manifested a “tribalism rooted in an identity politics of “blacker than thou, more dedicated than thou and more revolutionary than thou” which only deepened the fragmentation. The point that Payne (2007) brings to bear is that a de-emphasis on an interracial fellowship and an overt emphasis on racial consciousness, perhaps unintentionally, kindled racial tensions. Julius Bond (1999) who acknowledged the role of Black Power in fomenting the discord described this tension poignantly:

“This sharp line was drawn between black and white people in SNCC. It was extremely painful for many people on both sides because there were friendships going back three, four, five years, shared experiences, shared terror, shared danger. It was just rough for people to make an accommodation to this, and not everyone made an accommodation. It eventually helped to destroy us.

At a macro level of race relations beyond SNCC and CORE, this racial animosity intensified after King’s assassination when dreams of a Beloved Community gave way to cry of Black Power; it was manifested in various ways such as in the hostility that black communities harboured towards interracial marriages where it came to be perceived as a threat to racial purity and solidarity (Romano, 2009, 226; Farber, 2011). In the words of Martha Biondi (2012, 28), “black nationalism married the repudiation of interracial dating with authentic blackness”, and this led to a situation where an abstract racial concept of blackness came to become the criteria for exclusion and participation. Biondi (2012) observes that the new identity politics of racial consciousness rooted in Black Power became a barrier for interracial relationships on campuses and it held those engaged in interracial relationships suspect. However, where this ideological direction of racial consciousness of Black Power most differed significantly from King’s Beloved Community was in equating black manhood to self-dense and the over-emphasis of violence as a legitimate means of social change (Hill, 2004; Umoja; 2013; Strain, 2005) which corresponded with an attenuation of an affirmative political language of mutual belonging. In this regard, the valorisation and glorification of violence (Strain, 2005, 177; Watts, 2001, 326,) that followed the Black Power discourse, as embodied in the rhetoric and images of the post King’s Civil Rights Movement new SNCC leadership and groups such as the Black Panthers came to assume a mythical stature that transcend the logic of self-defence. Karenga, a leading black nationalist described this centrality of armed struggle accordingly (www.pbs.orgl, “the gun had become elevated to the concept of a political God. You solved problems with it.” Hill (2004) argues that the rhetoric of violence and militancy created a political identity that gave black men a sense of self-respect and a ground for dignity, in light of the absence of State protection. For Hill (2004) and Strain (2005) self-defence was instrumental in reinforcing the demands of the Civil Rights Movement, and in providing protection to local activists and communities who were denied the protection from the State, although the lines between self-defence, retaliation and revenge blurred. However, what is held suspect here is not the necessity of protecting local communities in the context of the racial terrorism, but, the culture of masculinity that emerged from this tradition of self-defence which linked manhood and dignity to self-defence and violence; in contrast to the theological motif of the Beloved Community that grounds human dignity in the fact that the human person was created in God’s image for eternal fellowship. In addition, the rivalry and violent conflict that erupted within circles of the Black Power movements (Komoki, 1999), which was fuelled by the State, further demonstrated how the identity politics of racial consciousness lacked the ability to produce a climate to affirm the mutual belonging even between people of the same racial group. This suggests that the absence of a political language of reconciliation embodied rhetorically and in a lived experience, constituted an impediment, particularly for SNCC initial dream of realising a Beloved Community because it devalued the role of love, and not race in struggling against oppression. Furthermore, this shows that in the context of a struggle for social political change rooted in a historical oppression and present State sanctioned and reactionary repression, a de-emphasis on reconciliation in terms of interpersonal relations between people with a history of division, and an over-emphasis on racial identity that is not situated in a vision of a mutual belonging, tends to create the condition for violence to flourish, regardless of how Noble and legitimate the cause of justice.

Freedom Seder: King’s assassination as an impetus for reconciliation

The second event which took place after Kings Assassination known as the Freedom Seder also represented a movement towards the Beloved Community that was rooted in a Jewish celebration of Passover. For Waskow, (2013), who invented the first Freedom Seder, a radical transformation of a religious ritual into an inclusive ceremony of belonging, King’s assassination was the event that rebirthed his commitment to justice and peace which his Jewish faith nurtured. As he put it:

“It all came like a volcano of reality exploding in me and around me, » Waskow recalled. « The whole structure of Jewish memories and teaching came together in my life. . . . Martin Luther King’s death rebirthed me."

The 1969 Freedom Seder which Waskow organised at a black church demonstrated the way in which King’s assassination created an opportunity for meaningful interracial and interfaith fellowship for the purpose of celebrating our shared humanity and reinforcing the struggle for racial justice. According to Waskow (1970), the Freedom Seder was not merely a ritual remembrance or even a shared promise for the future but rather a profound political act which carefully interwove the narrative of Jewish oppression with the Civil Rights and wider struggle for justice. The peculiarity of the 1969 Freedom Seder as a political act that continued King’s dream to realise a Beloved Community was embedded in the Haggadah, the text which accompanied the celebration of the Seder:

“The freedom we seek is a freedom from blood as well as a freedom from tyrants. It is incumbent upon us not only to remember in tears the blood of the tyrants and the blood of the prophets and martyrs, but to end the letting of blood. To end it, to end it!”

For as one of the greatest of our prophets, whose own death by violence at a time near the Passover were member in tears tonight as the prophet Martin Luther King called us to know: « The old law of an eye for an eye leaves everybody blind. It destroys community and makes brotherhood impossible. It creates bitterness in the survivors and brutality in the destroyers. But the principle of nonviolent resistance seeks to reconcile the truths of two opposites-acquiescence and violence.

By invoking the text above, the 1969 Freedom Seder can be said to be an attempt to recognize the historical wounds of oppression as well as a movement towards transforming the present oppression without violence; hence the emphasis on reconciliation and nonviolence. This presupposes that the 1969 Freedom Seder, by virtue of its interracial character and corresponding commensality, constituted a safe and non-threatening space to recognise the wounds of the oppressed and their desire for a new social order where human brotherhood can be a reality. Therefore to view the 1969 Freedom Seder as a thread of continuity in the Civil Rights Movement is to realize that its religious roots in the Jewish narrative of slavery mirrors the condition of oppression which assaulted the human dignity of the African American community. That the Freedom Seder, as a ritual of incarnating King’s memory has given rise to a plethora of Seders that hold annually across the US (Freedom Seder for Migration; Hunger Seder, 2012; Freedom Seder for the environment) demonstrates the positive impact of King’s assassination to create a space for members of divided communities to encounter one another and potentially discover a shared humanity. In its contextual particularity, the 1969 Freedom Seder can be invested with significant political value as a reconciliatory event that bears semblance to the Table of Brotherhood King envisioned where “Former slaves and slave owner would sit in brotherhood”. (King, 1963, 4) This is to say that it created a space for an encounter between members of divided community where an ethic of mutual belonging can receive concrete embodiment through sharing of food and building of friendship, juxtaposed with the recognition of oppression and a commitment to justice. Therefore to construe the Freedom Seder as an extension of the Civil Rights Movement is to acquiesce with Vincent Harding (1987) that the “Black struggle for Freedom is at its heart a profoundly human quest for transformation, a constantly evolving movement towards personal integrity and towards new social structures filled with justice, equity and compassion”. In essence this invites us to recognise that the 1969 Freedom Seder and the subsequent Seders represent an attempt to create a safe and inclusive space where different communities converge, to affirm their mutual belonging as well as their commitment to resisting structures that assault human dignity. In this regard, the text of the 14th annual Freedom Seder at The University of Massachusetts Amherst the celebrating liberation, multicultural unity and interfaith understanding (2012) is most instructive in conveying this point:

“We fight so that someday this will be true, not just for people of African Diaspora, but all people of all cultures, of all religions, of all identities will be equal in every form of the word. We fight so the people who enter this world do not have to regret being born. We fight to make this world a better place than it is today. We participate in and share Freedom Seder with those who align themselves with our motives and goals. We collectively push towards Freedom, actual Freedom. Through Freedom Seder, we believe this is a small but necessary and important part of achieving this role”.

However, the extent that the Freedom Seder reflects the Beloved Community lies in its ability to embody and point towards a self-giving and reconciling love that actively works to affirm human dignity, and overcome enmity regardless of the social, political, economic or cultural context. If such love is to be viewed as the central agency that build the Beloved Community, then it cannot merely be theoretical, abstract or ceremonial but must involve a social engagement that must be intentional in “implementing the demands of justice and correcting everything that stands against Love” (King, 2000, 325). This is precisely the point that theologian Linda Lee makes when she locates the starting point of the Beloved Community in the face to face, engagement with people over a long time; in essence, the relational. Therefore it is in this sense that the various creative enactment of the Freedom Seder-to welcome immigrants and refugees (Jewish Council on Urban Affairs, 2012), to serve as a bridge of interfaith understanding and racial reconciliation and to call for a greater stewardship for the environment, can all be conceived as a thread of continuity in the Civil Rights Movement to realise the Beloved Community without using violence This is because at its core, King’s Beloved Community mirrors a lived and living story of the self-giving, sacrificial and radical love of God through Jesus Christ which declares, unapologetically that: “God does not want to be God without the other-humanity” (Volf, 1996, 154). The thrust of vulnerability at the heart of this story is revealed in God’s movement towards his enemy to initiate friendship with the risk of rejection and without any assurance of a final reconciliation; a journey which ultimately exposes him to violence. This Love is most visibly dramatized at the Eucharist, the banqueting table of friendship where God breaks bread, joyfully in a gesture of hospitality that “welcomes the other in his or her unique position, need and potential.” (Wirzba, 2011, 167).